Navigating the Skies with Asthma or COPD: A Guide to Safe Air Travel

- OliveHealth

- Sep 13

- 5 min read

by Ed Fuentes, D.O.

For millions of people, air travel is a gateway to new adventures, family reunions, and professional opportunities. But for individuals living with a chronic respiratory condition like Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) or asthma, the journey itself can present unique challenges. The key to a safe and comfortable trip is not luck, but meticulous planning and a strong partnership with your healthcare provider.

This guide explores the physiological effects of flying and provides a comprehensive checklist to ensure that your health remains your top priority, from the moment you book your ticket to the moment you arrive at your destination.

The Air Up There: Understanding the Cabin Environment

The air in an airplane cabin is fundamentally different from the air on the ground. While your flight may cruise at altitudes of 36,000 feet or more, the cabin is pressurized to a much lower altitude, typically the equivalent of 8,000 feet . This is physiologically similar to being on a mountaintop, and it can affect anyone, but it poses a particular risk for people with pre-existing respiratory conditions.1

The primary physiological effects are:

Reduced Oxygen: The air on the plane still contains 21% oxygen, but the lower atmospheric pressure means there is a lower partial pressure of oxygen.3 For a healthy person, this drop is minimal, but for someone with compromised lung function, this can lead to a significant and dangerous drop in oxygen levels.1 The body's demand for oxygen also increases with physical activity, such as walking to the lavatory, which can lead to acute breathing difficulties on the plane.5

Trapped Gas Expansion: According to a principle known as Boyle's Law, gas expands as air pressure decreases.5 This is what causes common discomforts like ear and sinus pressure.8 However, for a patient with COPD who has bullous emphysema—large, air-filled sacs in the lungs—the expansion of trapped air can cause the sacs to rupture, potentially leading to a life-threatening collapsed lung, known as a pneumothorax.5

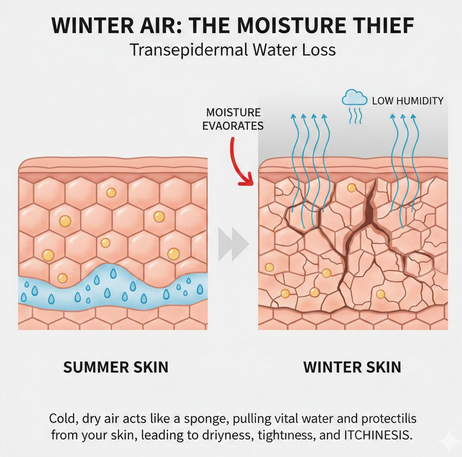

Low Humidity and Other Triggers: The cabin air is extremely dry, often with humidity levels as low as 5-15%.11 This can cause dehydration and dry out the mucous membranes in the respiratory tract, weakening the body's natural defenses against airborne irritants and germs.13 Simple measures like drinking plenty of water and wearing a mask can help mitigate this risk.15 Other triggers like dust, mold, and fumes can also be present in the cabin air.13

The Doctor's Office: A Non-Negotiable First Stop

The single most important step for anyone with a chronic respiratory condition is to consult with a physician for a pre-flight assessment.8 Air travel should be deferred if your condition is unstable, you have a recent lung infection, or you are experiencing an acute exacerbation.17

A thorough assessment will determine if you are fit to fly and whether you will need in-flight oxygen. Common screening tools include:

Resting Pulse Oximetry: A quick, non-invasive test that measures your blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂).2 A resting SpO₂ of >95% suggests a low risk for in-flight hypoxemia.2 However, a resting SpO₂ between 92% and 95% does not reliably predict in-flight complications, as many patients in this range can still experience a significant drop in oxygen saturation during flight.2

Walk Tests: The 6-minute walk test can assess your cardiopulmonary reserve under exertion.18 A patient who can walk 50 meters or climb a flight of stairs without severe distress is generally considered to have sufficient reserve for flying.8

High-Altitude Simulation Test (HAST): For patients in the intermediate-risk category, the HAST is considered the most accurate and reliable way to determine the need for supplemental oxygen.20 The test involves breathing a reduced oxygen mixture, typically 15%, to simulate the cabin environment.2 The results will determine the precise flow rate of oxygen needed to maintain a safe blood oxygen level.2 The test is also recommended for children with chronic lung conditions whose lung function (FEV₁) is consistently below 50%.24

The Prepared Traveler's Checklist

Once your medical provider has given you clearance to fly, the next step is meticulous logistical preparation.

Medications and Equipment: Always pack all medications, especially your quick-relief and daily controller inhalers, in your carry-on bag.13 This ensures they are accessible and are not lost or delayed with checked luggage.13 If you use a nebulizer, check with the airline to confirm their policy for in-flight use.13 TSA allows medically necessary liquids and aerosols for nebulizers in quantities greater than the standard limit, provided you declare them for inspection.28

Portable Oxygen Concentrators (POCs): Airlines do not provide oxygen cylinders or canisters on board. The responsibility for all medical equipment lies with the passenger.11 Most airlines permit the use of FAA-approved POCs, but they have strict, non-negotiable rules. The most critical requirement is that you must have enough charged batteries to power your device for at least 150% of the expected flight duration. You must also notify the airline in advance, typically 48 to 72 hours before your flight.

Medical Documentation: Carry a letter from your physician outlining your diagnosis, a list of your medications (including generic names), and any medical equipment you use.13 This is crucial for navigating airport security and for seeking medical care at your destination.13 For children with asthma, an updated asthma action plan with the doctor's contact information should also be carried.

In-Flight and Destination Tips

Hydration: Drink plenty of water throughout the flight to combat the effects of dry cabin air, and avoid alcohol and caffeine, which can lead to dehydration.

Managing Triggers: Wear a mask to reduce the risk of infection and turn on the air vent above your seat to create a personal zone of filtered air.13

Stress Management: Travel can be stressful, and stress is a known trigger for asthma attack. Practice relaxation techniques like deep breathing and try to maintain a healthy diet and sleep routine to help your body cope with the added stress of travel.

At Your Destination: Be prepared for potential triggers at your destination. Check local pollen counts and air quality indexes, and consider requesting a non-smoking, pet-free room at your hotel.13

By following these recommendations, you can take control of your journey and reduce the risk of complications. Your ultimate goal is a safe and enjoyable trip, and a little preparation can go a long way in making that happen.

References:

Comments